Towards Embodied AI with MuscleMimic: Unlocking full-body musculoskeletal motor learning at scale

An open-source framework for scalable motion imitation learning with physiologically realistic, muscle-actuated humanoids.

Human motor control emerges from hundreds of muscles coordinating in real time, yet most simulated humanoids bypass this complexity entirely, relying on torque-driven joints that ignore the underlying neuromotor dynamics

MuscleMimic is an open-source framework that changes this. By combining full-body muscle-actuated humanoids with massively parallel GPU simulation via MuJoCo Warp

Preprint of this work will be released soon

Code, checkpoints, and retargeted dataset: github.com/amathislab/musclemimic

Try out musculoskeletal models: pip install musclemimic_models

What It Looks Like

Imitation Learning Results

We evaluate the generalist policy on the KINESIS motion dataset using early termination as the primary quality signal: an episode terminates if the mean site deviation across 17 mimic sites relative to the root (pelvis) exceeds 0.3 m, or if the pelvis deviates from the reference by more than 0.5 m in world coordinates. We use relative rather than absolute position error because muscle activation dynamics introduce temporal delays that prevent the musculoskeletal model from perfectly tracking reference velocities.

| Metric | GMR-Fit (Train) | GMR-Fit (Test) |

|---|---|---|

| Early termination rate | 0.108 | 0.129 |

| Joint position error | 0.129 | 0.130 |

| Joint velocity error | 0.542 | 0.545 |

| Root position error | 0.079 | 0.138 |

| Root yaw error | 0.048 | 0.047 |

| Relative site position error | 0.027 | 0.027 |

| Absolute site position error | 0.144 | 0.146 |

| Mean episode length | 534.1 | 528.1 |

| Mean episode return | 575.9 | 569.1 |

Validation metrics on KINESIS training (972 motions) and testing (108 motions) dataset.

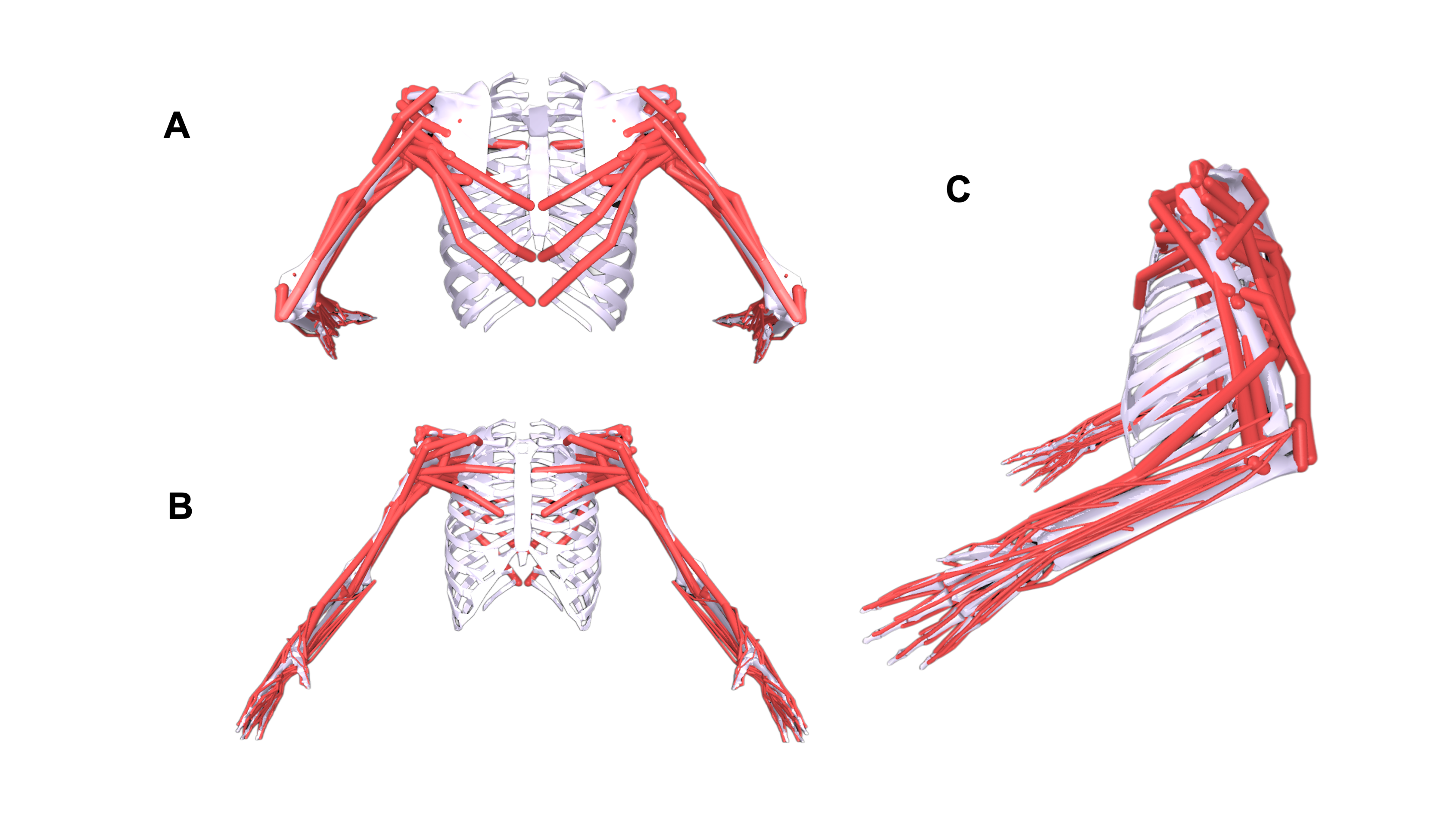

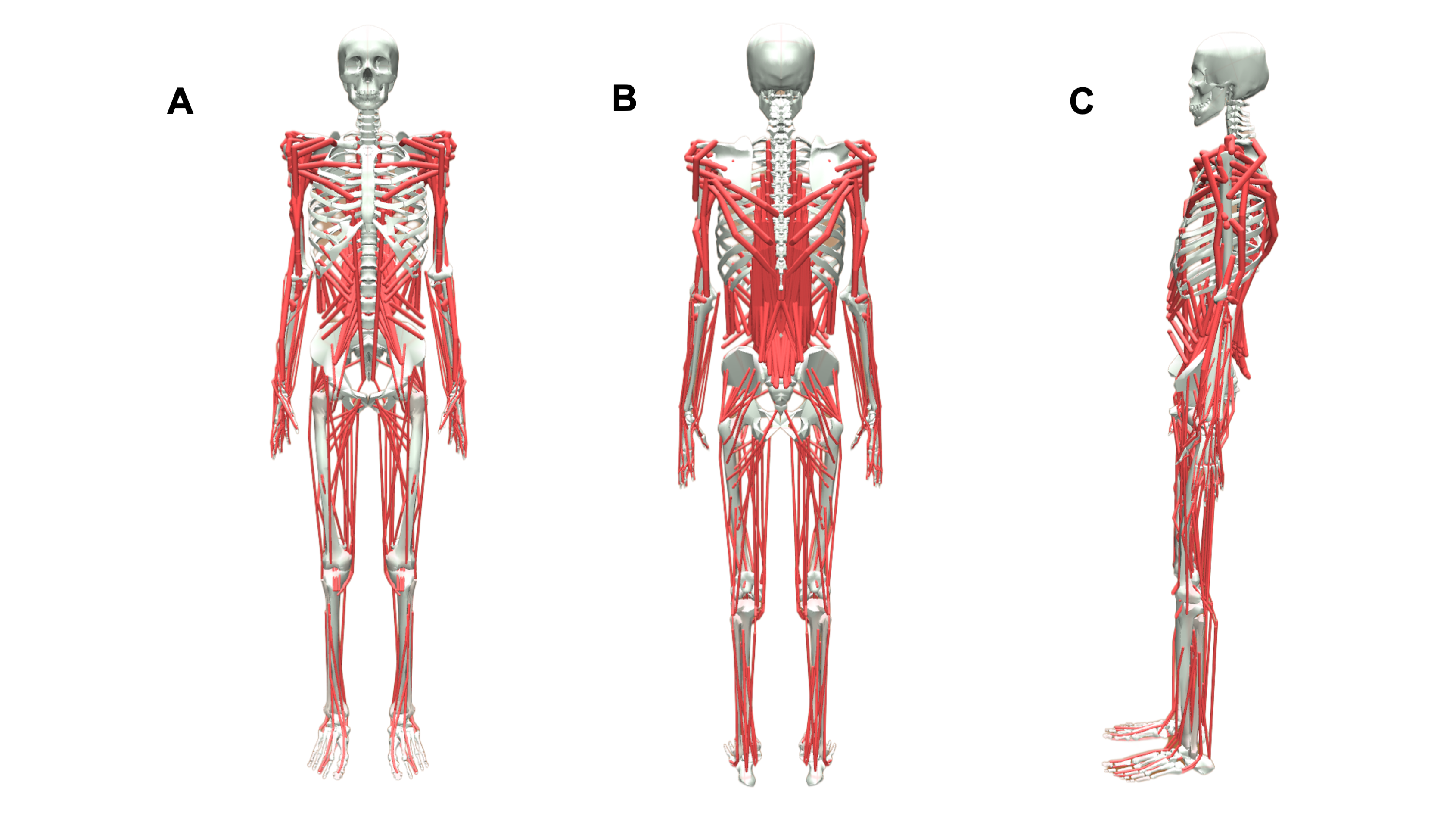

The Models

MuscleMimic introduces two complementary musculoskeletal embodiments for motion learning centered on manipulation or locomotion.

| Model | Type | Joints | Muscles | DoFs | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BimanualMuscle | Fixed-base | 76 (36*) | 126 (64*) | 54 (14*) | Upper-body manipulation |

| MyoFullBody | Free-root | 123 (83*) | 416 (354*) | 72 (32*) | Locomotion and manipulation |

* denotes configurations with finger muscles disabled for faster convergence. Joints denote articulated connections; DoFs correspond to independently controllable joint coordinates.

Both models are built upon established MyoSuite components

Validation Against Human Data

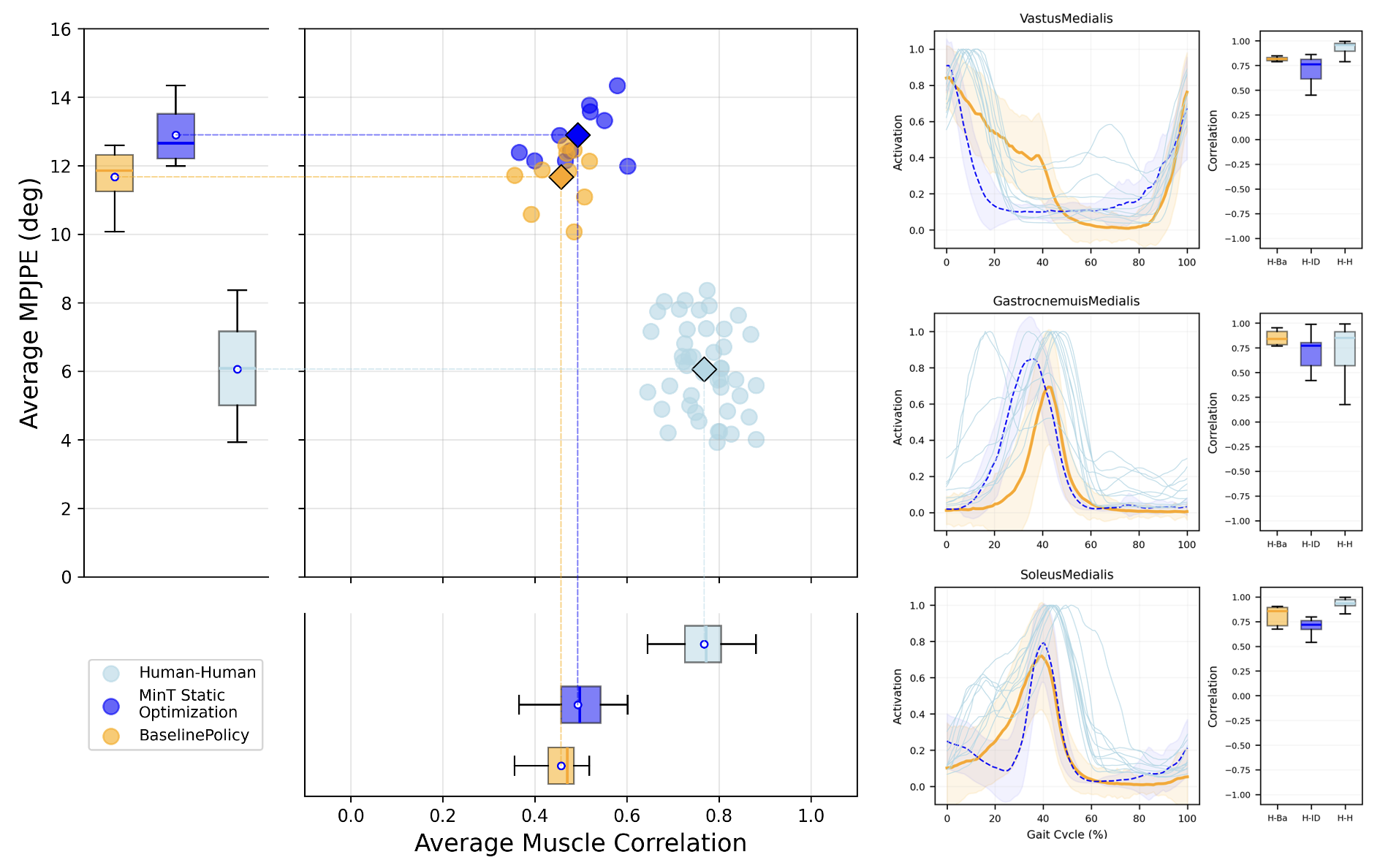

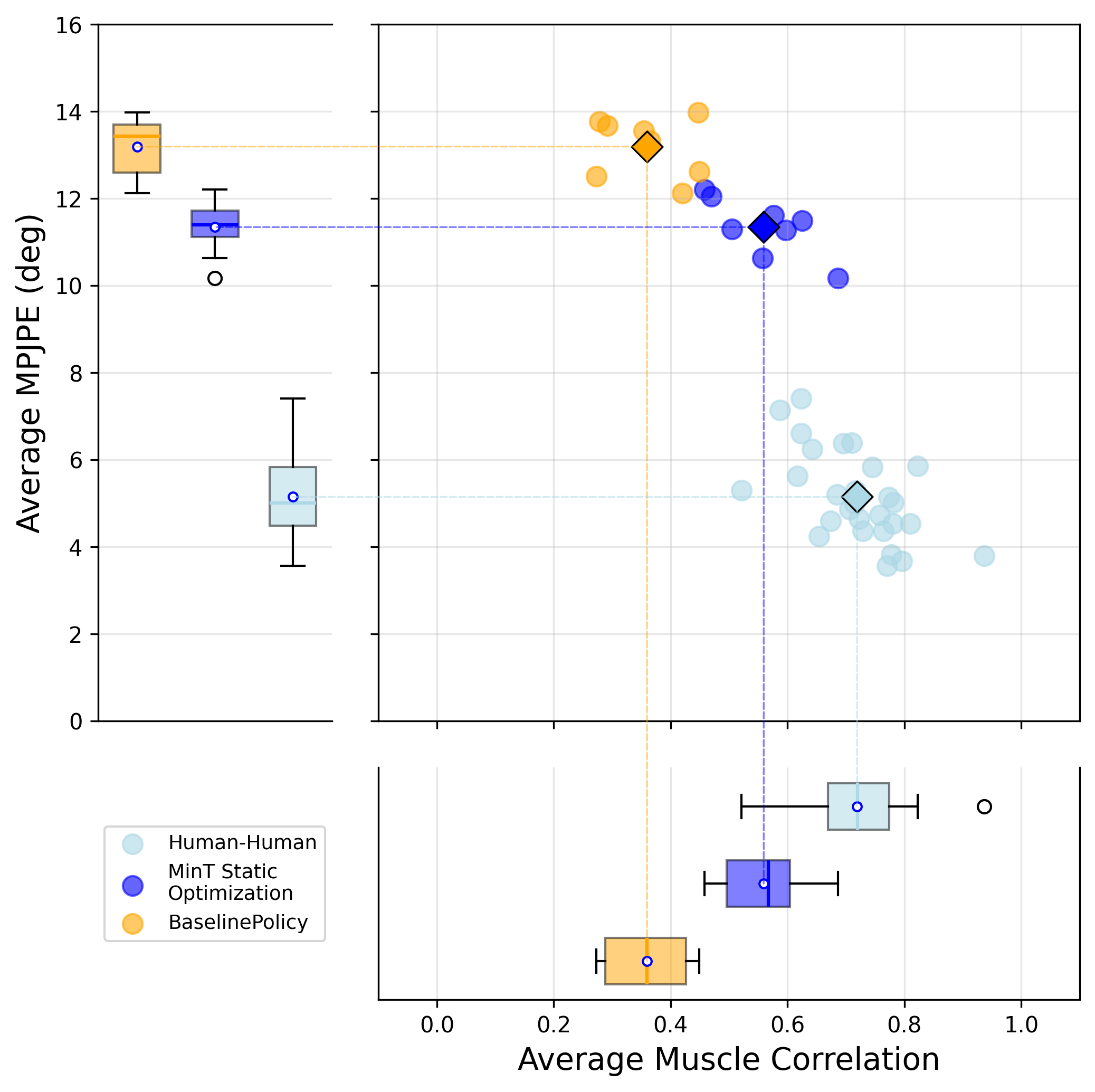

To verify the biomechanical fidelity of our models during dynamic motion, we conduct population-based evaluations on walking and running against human experimental data on joint kinematics, kinetics, and EMG, as suggested in

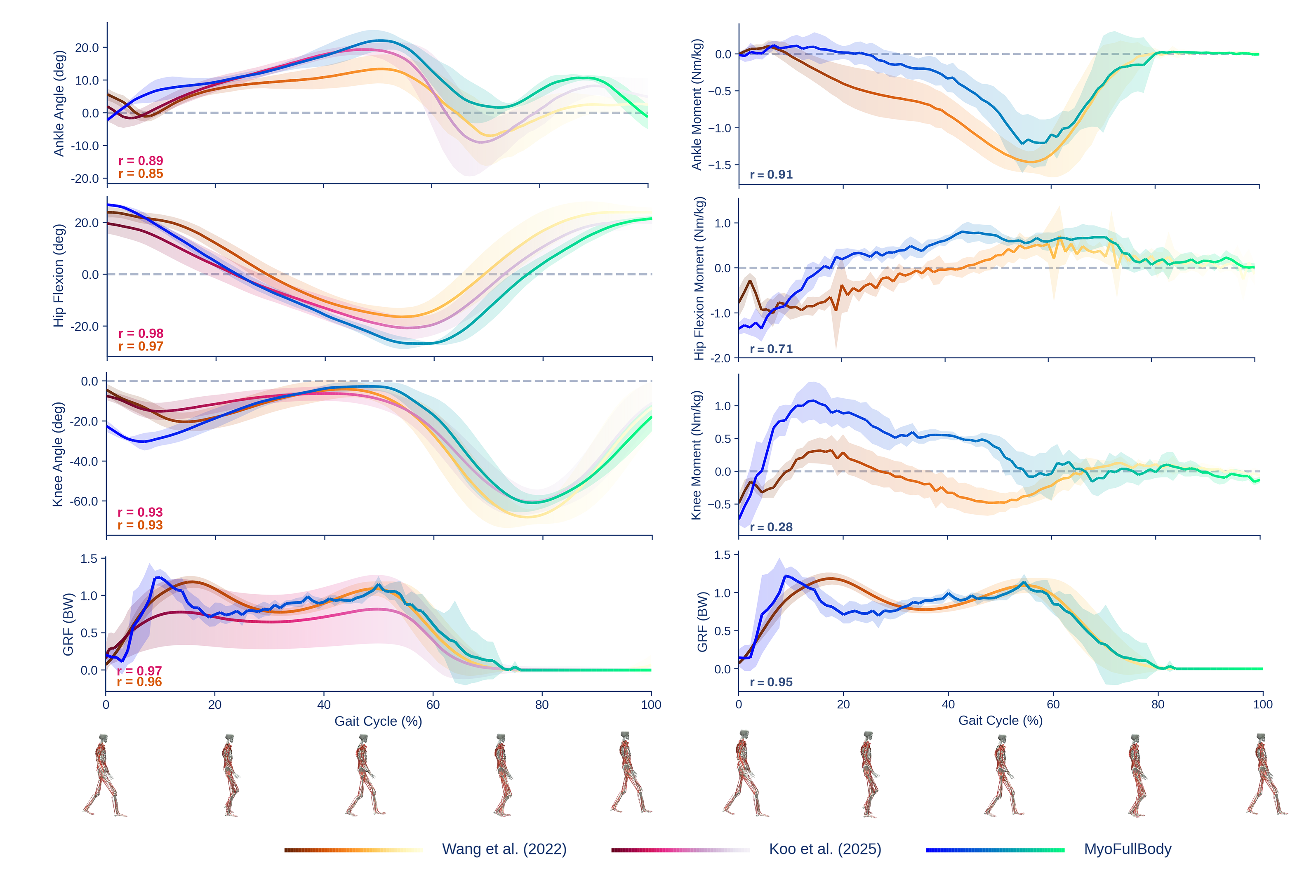

Walking

We evaluate on five AMASS walking sequences, comparing against two experimental datasets (treadmill and level walking at 1.2 m/s, nine participants each of two datasets

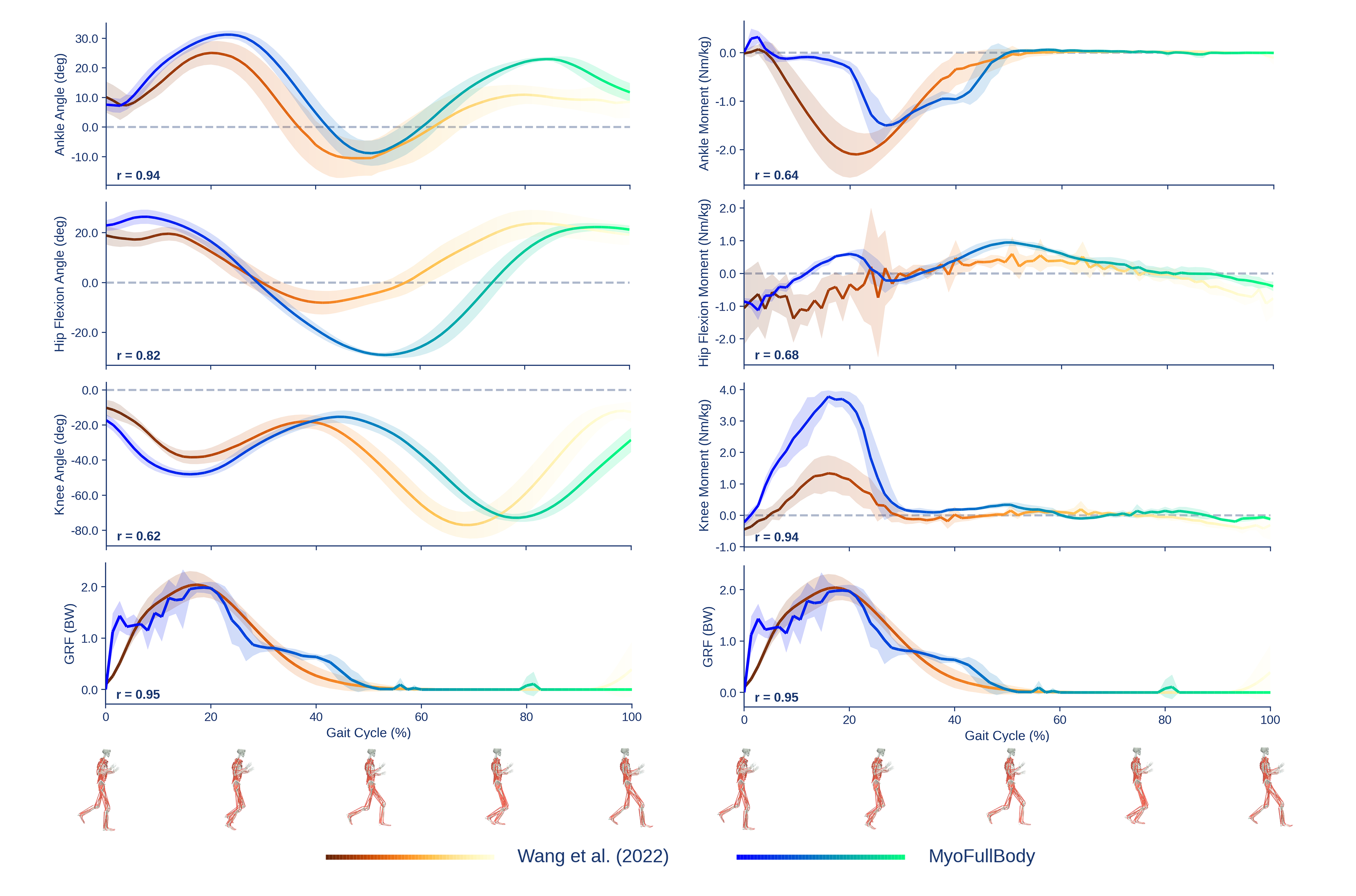

Running

After fine-tuning the 10-billion-step checkpoint with an additional 50 million steps on 10 running motions, we compare against treadmill-running data at 1.75 m/s from Wang et al.

EMG

We compare synthetic muscle activations against EMG recordings from two human walking datasets

How It Works

Musculoskeletal Model

Both embodiments use Hill-type

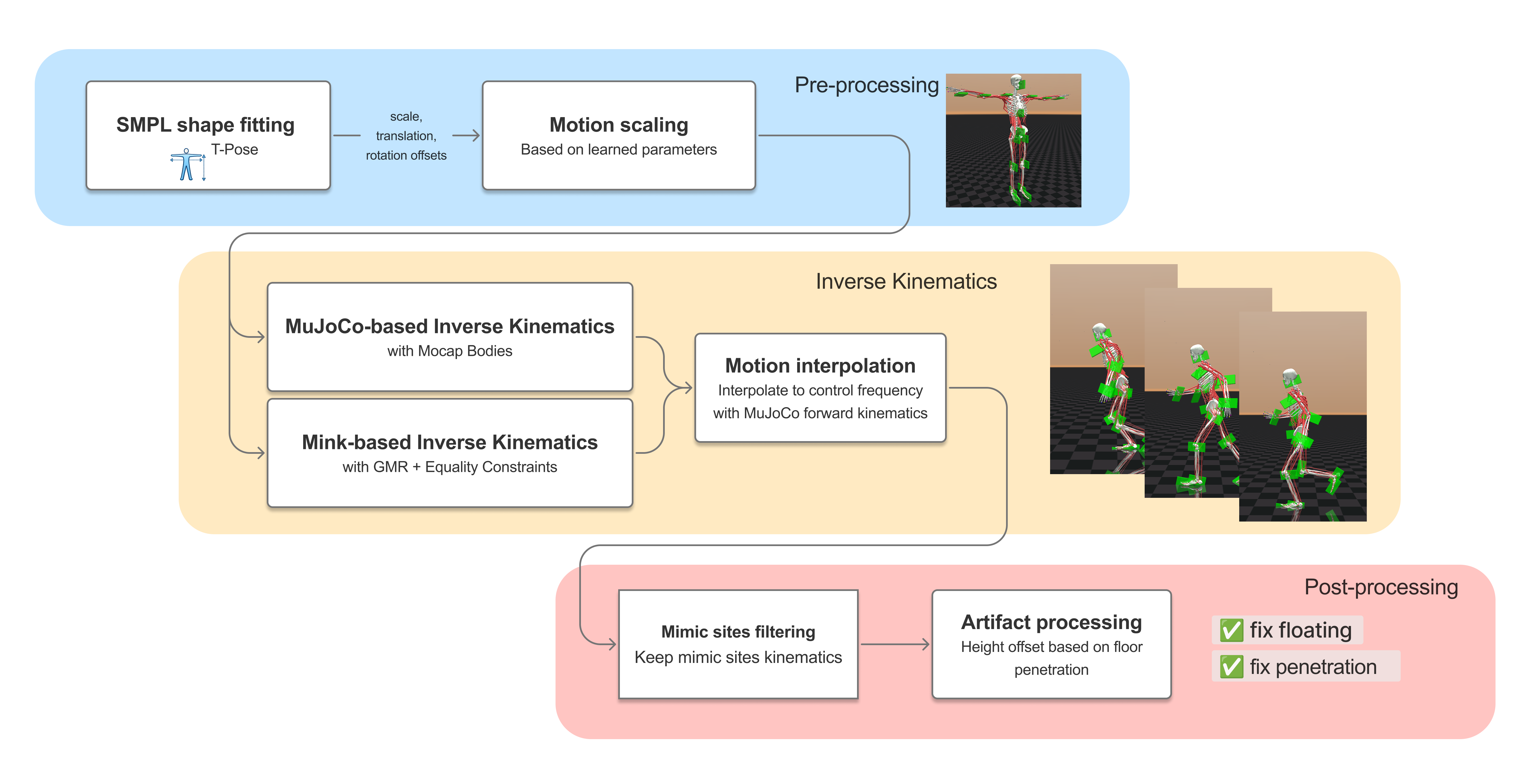

Motion Retargeting

We provide two retargeting pipelines that map SMPL-format motion capture data onto the musculoskeletal models. Mocap-Body uses a kinematic body in MuJoCo with a three-stage pipeline: SMPL shape fitting, inverse kinematics, and post-processing to remove artifacts such as floating and ground penetration. GMR-Fit

| Metric | Mocap-Body | GMR-Fit |

|---|---|---|

| Joint limit violation (%) | 12.26 | 0.27 |

| Ground penetration (%) | 0.55 | 0.24 |

| Max penetration (m) | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Tendon jump rate (%) | 30.14 | 3.20 |

| RMSE (m) | 0.039 | 0.025 |

| Speed per frame (s) | 0.076 | 0.251 |

GMR-Fit achieves dramatically better joint-limit satisfaction (0.27% vs 12.26% violation) and lower tendon jump rates (3.20% vs 30.14%), while Mocap-Body retains a ~3x speed advantage.

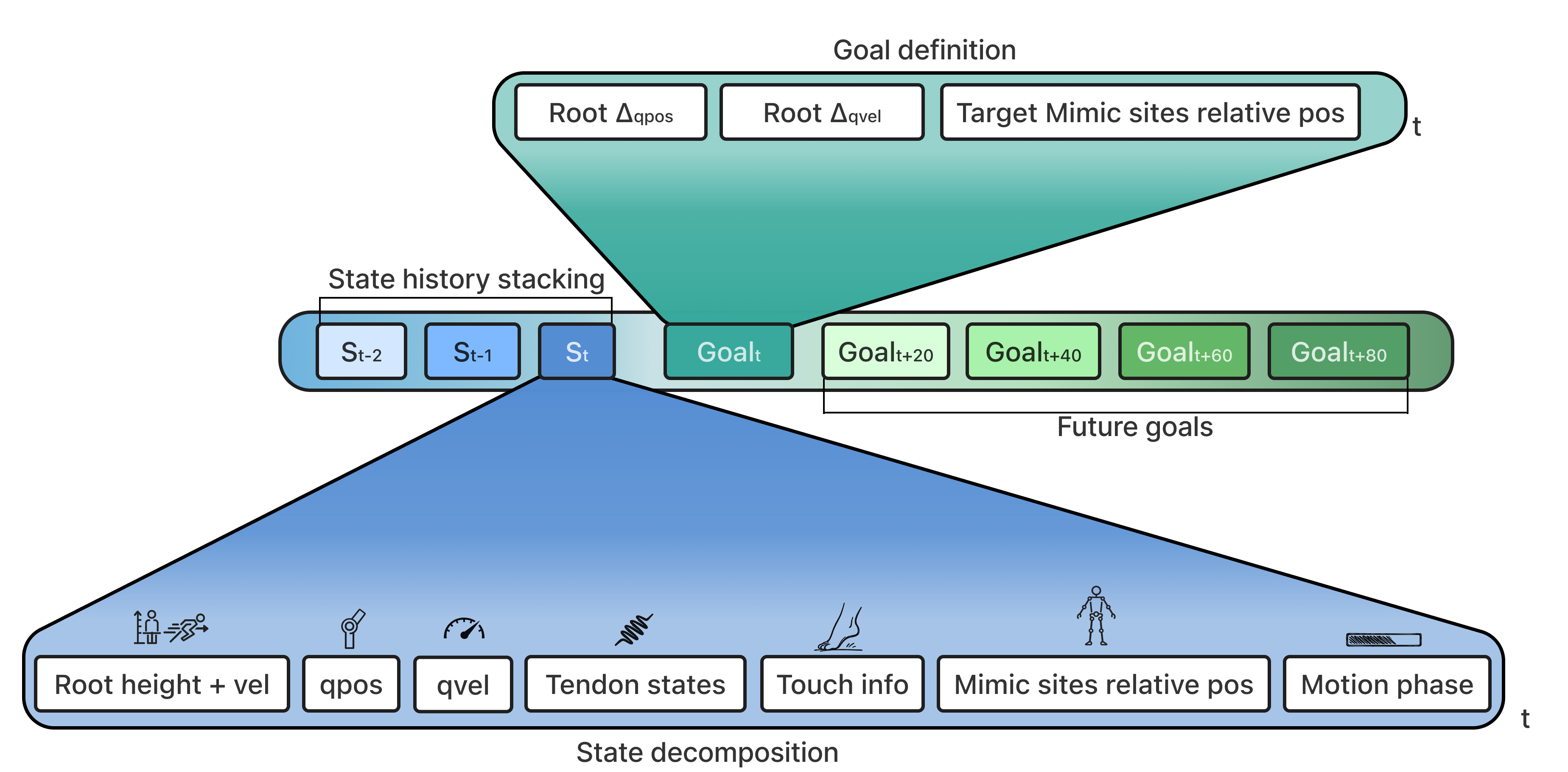

Policy

The policy is an MLP with residual connections that outputs $\pi(a_t \mid s_t)$, a distribution over muscle excitation. The observation $s_t$ includes proprioceptive signals, tendon states, motion targets, and crucially, the previous policy output $a_{t-1}$, making it autoregressive in nature. Both actor and critic use SiLU activations

Reward

The reward at each timestep is $r_t = \max(0,\; r_t^{\text{imit}} + P_t)$, combining an imitation term with a penalty. The imitation reward is a weighted sum of six exponential-kernel terms, all computed relative to the pelvis rather than in world frame.

The penalty $P_t = \max(-1,\; -\sum \lambda_p C_p)$ regularizes action bounds violations, action rate, and muscle activation energy.

Training at Scale

MuscleMimic is implemented as a JAX-based framework extending LocoMuJoCo

For large scale training, we use the Muon optimizer

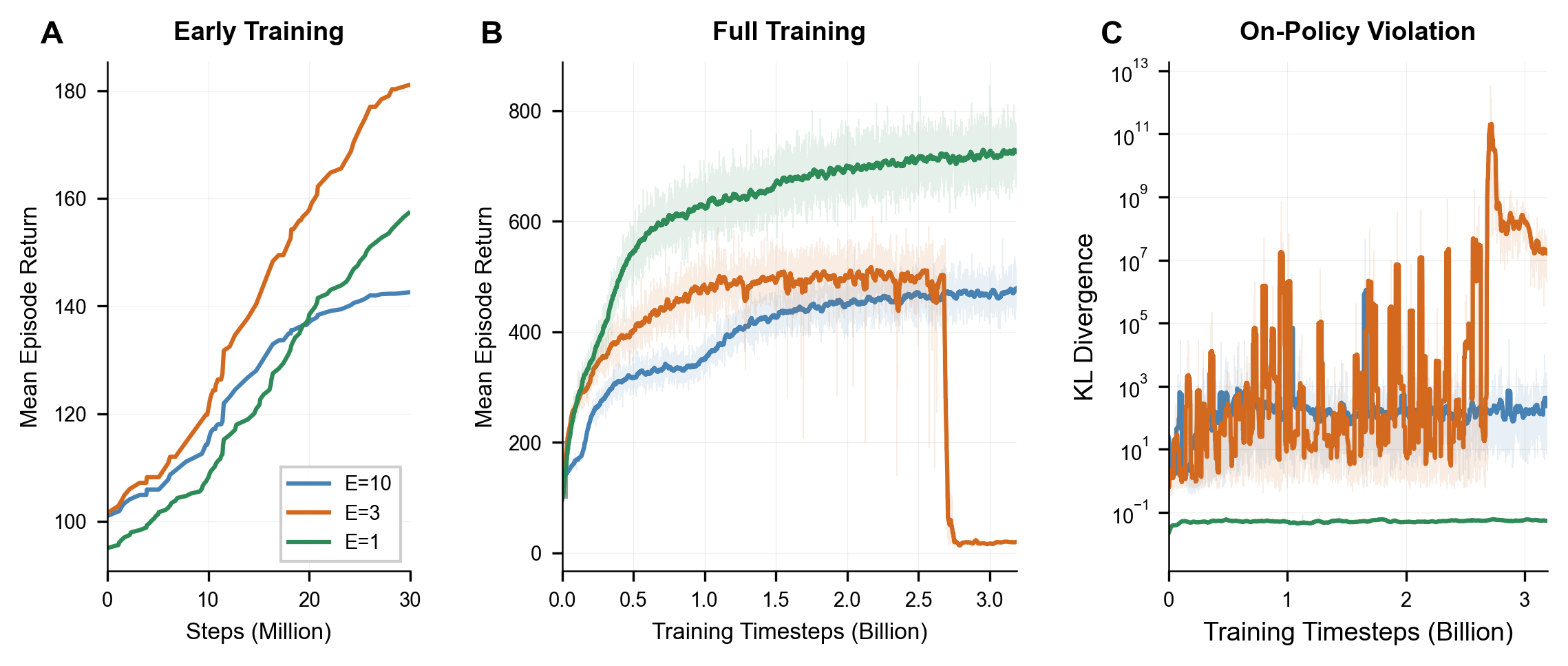

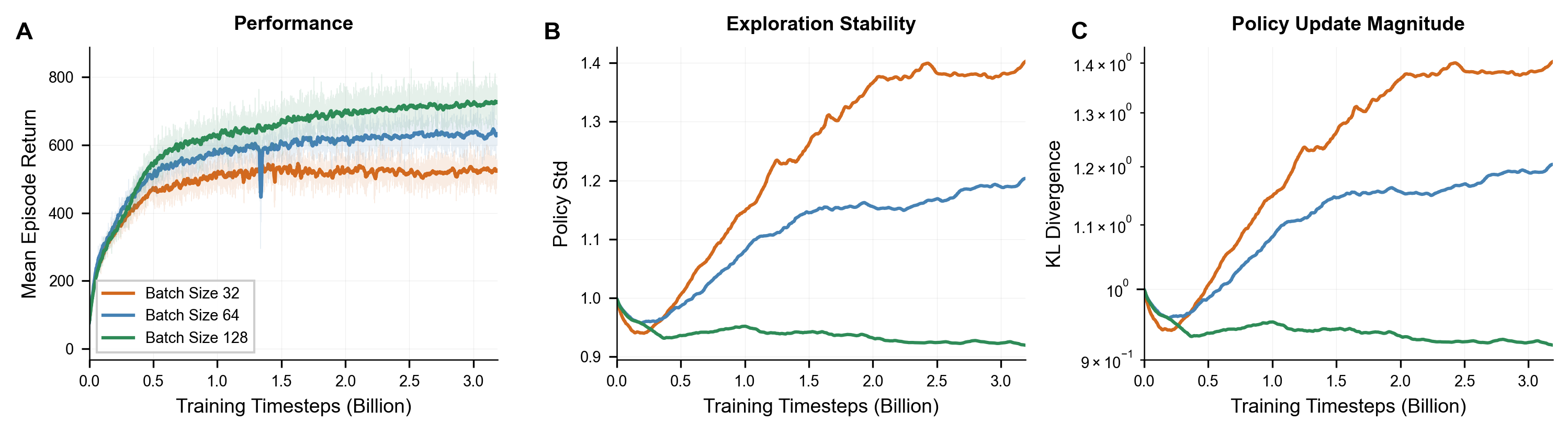

Single-epoch updates work best. With massively parallel GPU simulation, we can collect fresh data cheaply, so single-epoch updates ($E = 1$) achieve superior asymptotic performance while avoiding pathologies from aggressive sample reuse: expert collapse in Soft MoE routing and severe distribution shift with KL divergence spikes orders of magnitude above the stable baseline.

Larger batch sizes improve stability. Larger batch sizes yield higher asymptotic rewards, lower KL divergence, and smoother convergence. Since larger batches require fewer gradient updates per environment step, training is also faster in wall-clock time.

Training throughput scales directly with GPU hardware. Newer architectures such as NVIDIA H200 provide significant speedups in both simulation and gradient computation.

Model Validation

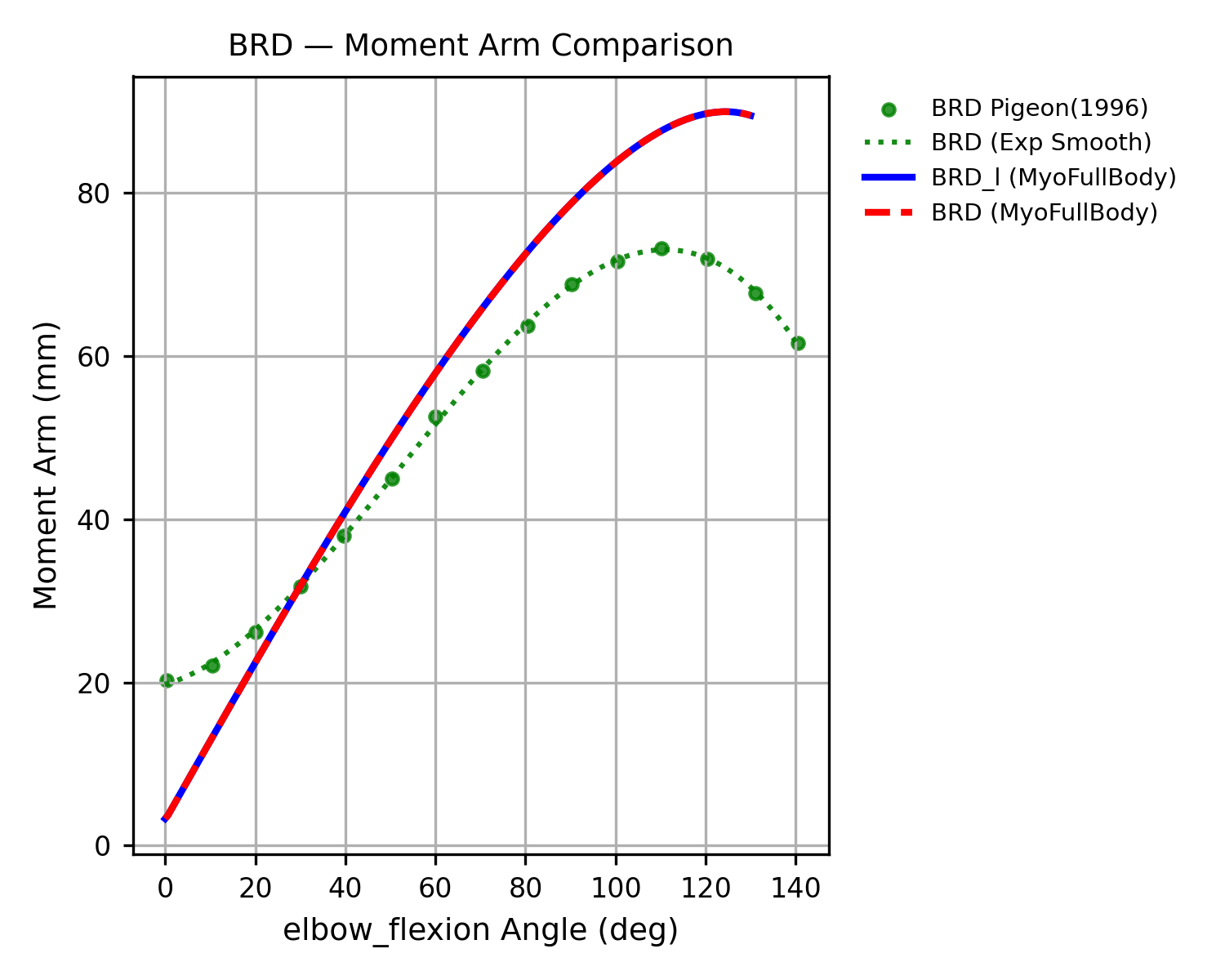

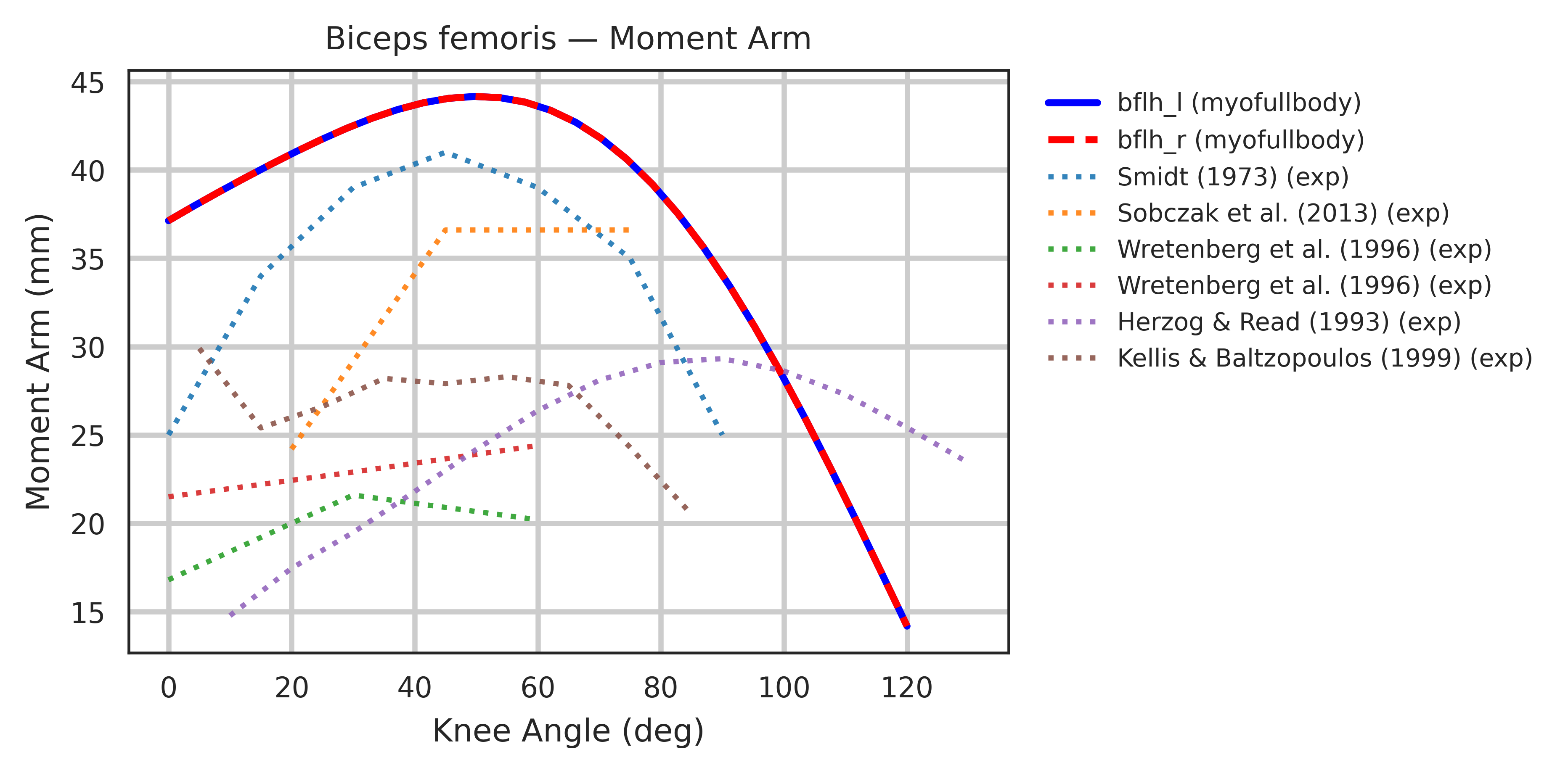

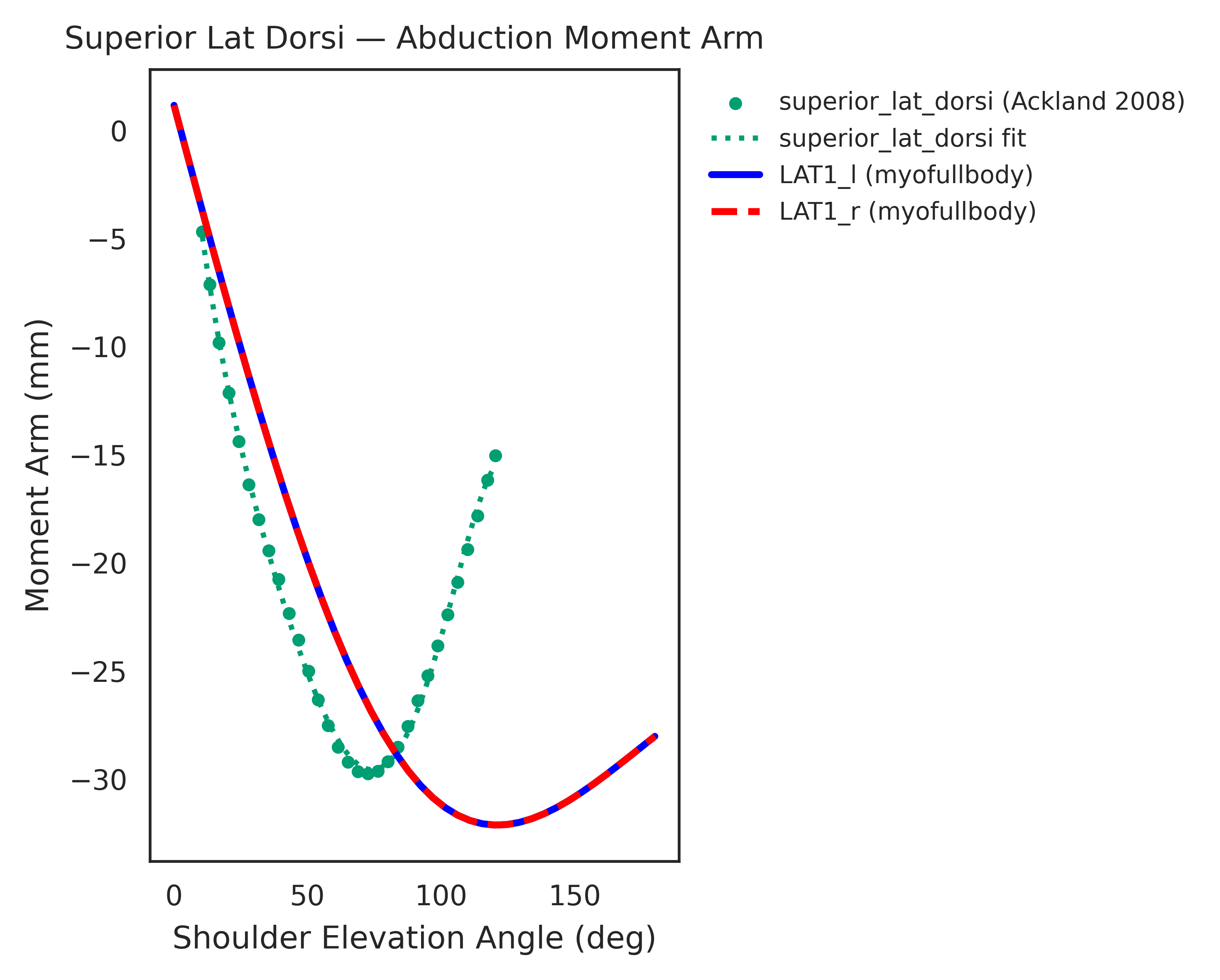

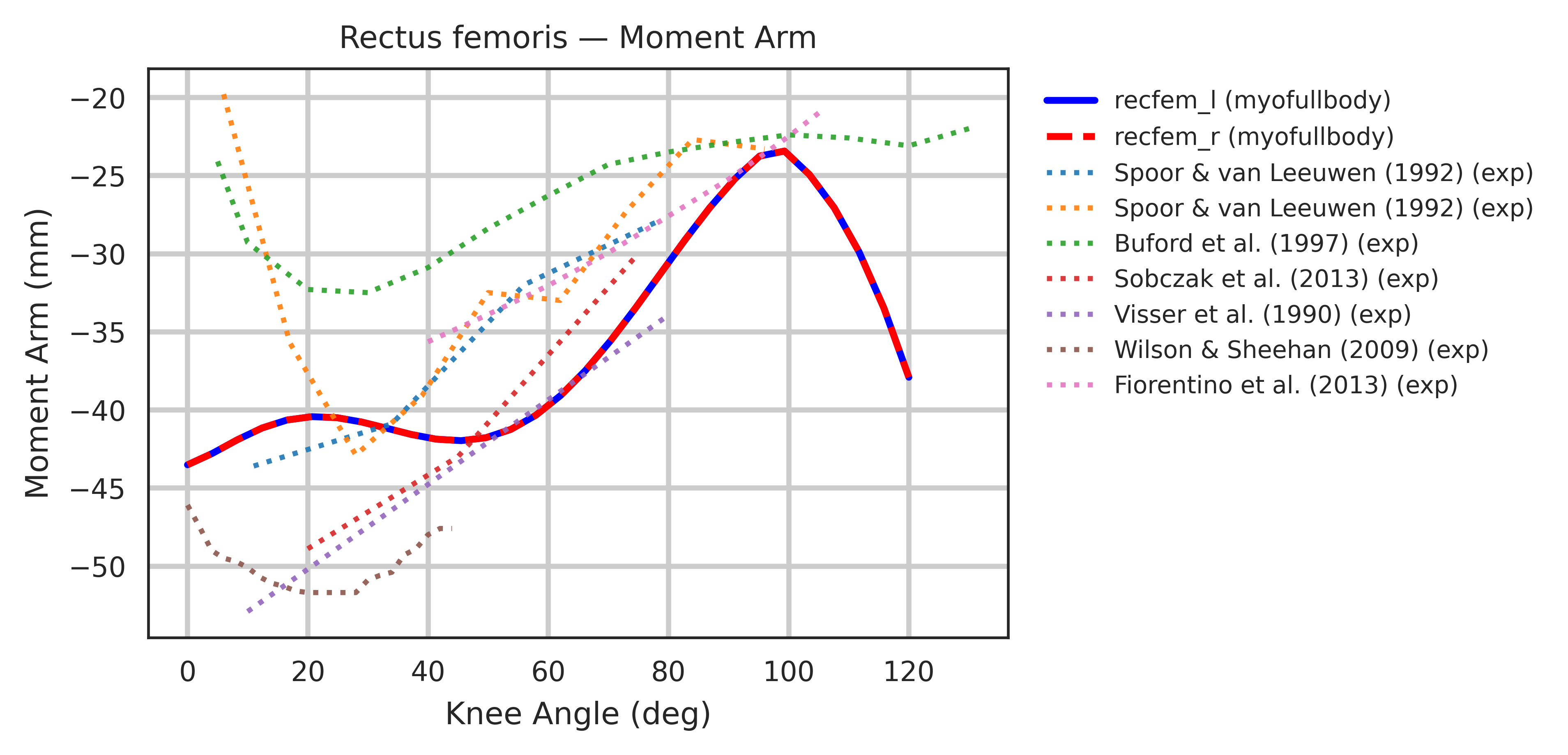

Both models were extensively validated for muscle symmetry and biomechanical accuracy. Each muscle-tendon moment arm was cross-validated against its target joint to ensure smooth, continuous profiles, with wrapping geometries manually corrected whenever discontinuities were found. Most refinement concentrated around the shoulder joint, where multiple equality constraints are enforced.

Moment arms were further validated against experimental measurements from cadaver and MRI studies

Limitations

While our framework demonstrates promising alignment with experimental data, musculoskeletal models remain approximations of biological reality. For example, the Hill-type model in MuJoCo simplifies complex phenomena such as history-dependent force production, heterogeneous fiber recruitment, and tendon elasticity. These assumptions can influence dynamic outcomes and may limit the faithful reproduction of highly explosive or high-impact motions (e.g., martial arts or rapid vertical jumping). Moreover, the current SMPL-based retargeting pipeline assumes generic morphology and matched gender, leaving open questions about how subject-specific anthropometrics affect retargeting accuracy and policy learning. Simulation results at the current stage should therefore be interpreted as model-based predictions and validated against experimental data before clinical applications.

By open-sourcing this framework, we invite the community to iterate on these models: refining muscle parameters, improving joint definitions, and validating against diverse experimental datasets. We also encourage researchers to explore future applications in rehabilitation and human–robot interaction, including training on pathological gait patterns and integration with assistive devices such as exoskeletons.

Preprint of this work will be released soon

Code, checkpoints, and retargeted dataset: github.com/amathislab/musclemimic

Try out musculoskeletal models: pip install musclemimic_models

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Mathis Group for feedback on the project, and Vittorio Caggiano, James Heald, and Balint K. Hodossy for helpful discussions.

Citation

Please cite this work as

@article{musclemimic2026,

title = {Towards Embodied AI with MuscleMimic: Unlocking full-body musculoskeletal motor learning at scale},

author = {Chengkun Li and Cheryl Wang and Bianca Ziliotto and Merkourios Simos and Guillaume Durandau and Alexander Mathis},

year = {2026},

}